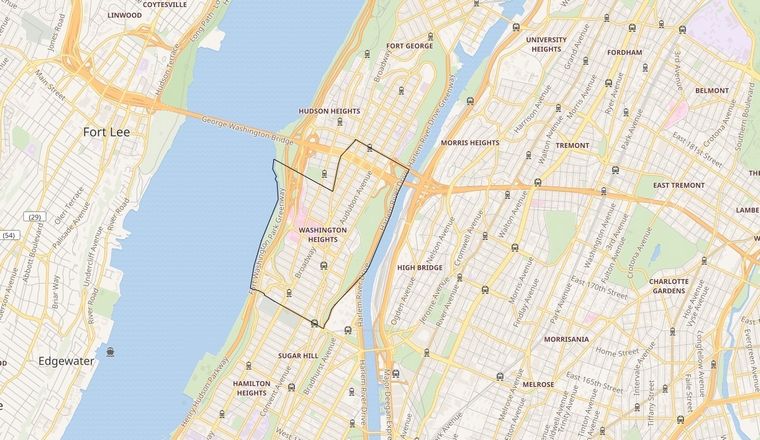

Washington Heights is a neighborhood in the northern portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan. The area, with over 150,000 inhabitants as of 2010, is named for Fort Washington, a fortification constructed at the highest point on Manhattan island by Continental Army troops during the American Revolutionary War, to defend the area from the British forces. Washington Heights is bordered by Harlem to the south, along 155th Street, Inwood to the north along Hillside Avenue, the Hudson River to the west, and the Harlem River and Coogan’s Bluff to the east.

Early history

In the 18th century, only the southern portion of the island was settled by Europeans, leaving the rest of Manhattan largely untouched. Among the many unspoiled tracts of land was the highest spot on the island, which provided unsurpassed views of what would become the New York metropolitan area.

When the Revolutionary War came to New York, the British had the upper hand. General George Washington and troops from his Continental Army camped on the high ground, calling it Fort Washington, to monitor the advancing Redcoats. The Continental Army retreated from its location after their defeat on November 16, 1776, in the Battle of Fort Washington. The British took the position and renamed it Fort Knyphausen in honor of the leader of the Hessians, who had taken a major part in the British victory. Their location was in the spot now called Bennett Park. Fort Washington had been established as an offensive position to prevent British vessels from sailing north on the Hudson River. Fort Lee, across the river, was its twin, built to assist in the defense of the Hudson Valley. The progress of the battle is marked by a series of bronze plaques along Broadway.

Not far from the fort was the Blue Bell Tavern, located on an intersection of Kingsbridge Road, where Broadway and West 181st Street intersect today, on the southeastern corner of modern-day Hudson Heights. On July 9, 1776, when New York’s Provincial Congress assented to the Declaration of Independence, “A rowdy crowd of soldiers and civilians (‘no decent people’ were present, one witness said later) … marched down Broadway to Bowling Green, where they toppled the statue of George III erected in 1770. The head was put on a spike at the Blue Bell Tavern … “

The tavern was later used by Washington and his staff when the British evacuated New York, standing in front of it as they watched the American troops march south to retake New York.

By 1856 the first recorded home had been built on the site of Fort Washington. The Moorewood residence was there until the 1880s. The property was purchased by Richard Carman and sold to James Gordon Bennett Sr. for a summer estate in 1871. Bennett’s descendants later gave the land to the city to build a park honoring the Revolutionary War encampment. Bennett Park is a portion of that land. Lucius Chittenden, a New Orleans merchant, built a home on land he bought in 1846 west of what is now Cabrini Boulevard and West 187th Street. It was known as the Chittenden estate by 1864. C. P. Bucking named his home Pinehurst on land near the Hudson, a title that survives as Pinehurst Avenue.

The series of ridges overlooking the Hudson were sites of villas in the 19th century, including the extensive property of John James Audubon.

Early and mid-20th century

At the turn of the 20th century the woods started being chopped down to make way for homes. The cliffs that are now Fort Tryon Park held the mansion of Cornelius Kingsley Garrison Billings, a retired president of the Chicago Coke and Gas Company. He purchased 25 acres (100,000 m2) and constructed Tryon Hall, a Louis XIV-style home designed by Gus Lowell. It had a galleried entranceway from the Henry Hudson Parkway that was 50 feet (15 m) high and made of Maine granite. In 1917, Billings sold the land to John D. Rockefeller Jr. for $35,000 per acre. Tryon Hall was destroyed by fire in 1925. The estate was the basis for the book “The Dragon Murder Case” by S. S. Van Dine,in which detective Philo Vance had to solve a murder on the grounds of the estate, where a dragon was supposed to have lived.

In the early 1900s, Irish immigrants moved to Washington Heights. European Jews went to Washington Heights to escape Nazism during the 1930s and the 1940s. During the 1950s and 1960s, many Greeks moved to Washington Heights; the community was referred to as the “Astoria of Manhattan.” By the 1980s–90s, the neighborhood became mostly Dominican.

Fort Tryon

During World War I, immigrants from Hungary and Poland moved in next to the Irish. Then, as Naziism grew in Germany, Jews fled their homeland. By the late 1930s, more than 20,000 refugees from Germany had settled in Washington Heights.

The beginning of this section of Washington Heights as a neighborhood-within-a-neighborhood seems to have started around this time, in the years before World War II. One scholar refers to the area in 1940 as “Fort Tryon” and “the Fort Tryon area.” In 1989, Steven M. Lowenstein wrote, “The greatest social distance was to be found between the area in the northwest, just south of Fort Tryon Park, which was, and remains, the most prestigious section … This difference was already remarked in 1940, continued unabated in 1970 and was still noticeable even in 1980…” Lowenstein considered Fort Tryon to be the area west of Broadway, east of the Hudson, north of West 181st Street, and south of Dyckman Street, which includes Fort Tryon Park. He writes, “Within the core area of Washington Heights (between 155th Street and Dyckman Street) there was a considerable internal difference as well. The further north and west one went, the more prestigious the neighborhood…”

Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson

In the years after World War II, the neighborhood was referred to as Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson due to the dense population of German and Austrian Jews who had settled there. A disproportionately large number of Germans who settled in the area had come from Frankfurt-am-Main, possibly giving rise to new name.No other neighborhood in the city was home to so many German Jews, who had created their own central German world in the 1930s.

Stairs running from the end of Pinehurst Avenue down to West 181st Street

So cosmopolitan was that world that in 1934 members of the German-Jewish Club of New York started Aufbau, a newsletter for its members that grew into a newspaper. Its offices were nearby on Broadway. The newspaper became known as a “prominent intellectual voice and a main forum for German Jewry in the United States,” according to the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. “It featured the work of great prominent writers and intellectuals such as Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Stefan Zweig, and Hannah Arendt. It was one of the only newspapers to report on the atrocities of the Holocaust during World War II.”

In 1941, it published the Aufbau Almanac, a guide to living in the United States that explained the American political system, education, insurance law, the post office and sports. After the war, Aufbau helped families that had been scattered by European battles to reconnect by listing survivors’ names. Aufbau ’s offices eventually moved to the Upper West Side. The paper nearly went bankrupt in 2006, but was purchased by Jewish Media AG, and exists today as a monthly news magazine. Its editorial offices are now in Berlin, but it keeps a correspondent in New York.

When the children of the Jewish immigrants to the Hudson Heights area grew up, they tended to leave the neighborhood, and sometimes, the city. By 1960 German Jews accounted for only 16% of the population in Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson. The neighborhood became less overtly Jewish into the 1970s as Soviet immigrants moved to the area. After the Soviet immigration, families from the Caribbean, especially Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, made it their home. So many Dominicans live in Washington Heights that candidates for the presidency of the Dominican Republic campaign in parades in the area.) In the 1980s African-Americans began to moved in, followed shortly by other groups. “Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson” no longer described the area.