(Sexually Transmitted Diseases)

Human immunodeficiency virus infection / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a disease of the human immune system caused by infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). During the initial infection, a person may experience a brief period of influenza-like illness. This is typically followed by a prolonged period without symptoms. As the illness progresses, it interferes more and more with the immune system, making the person much more likely to get infections, including opportunistic infections and tumors that do not usually affect people who have working immune systems.

Human immunodeficiency virus infection / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a disease of the human immune system caused by infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). During the initial infection, a person may experience a brief period of influenza-like illness. This is typically followed by a prolonged period without symptoms. As the illness progresses, it interferes more and more with the immune system, making the person much more likely to get infections, including opportunistic infections and tumors that do not usually affect people who have working immune systems.

HIV is transmitted primarily via unprotected sexual intercourse (including anal and even oral sex), contaminated blood transfusions, hypodermic needles, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding. Some bodily fluids, such as saliva and tears, do not transmit HIV. Prevention of HIV infection, primarily through safe sex and needle-exchange programs, is a key strategy to control the spread of the disease. There is no cure or vaccine; however, antiretroviral treatment can slow the course of the disease and may lead to a near-normal life expectancy. While antiretroviral treatment reduces the risk of death and complications from the disease, these medications are expensive and may be associated with side effects.

Genetic research indicates that HIV originated in west-central Africa during the early twentieth century. AIDS was first recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1981 and its cause—HIV infection—was identified in the early part of the decade. Since its discovery, AIDS has caused nearly 30 million deaths (as of 2009). As of 2010, approximately 34 million people are living with HIV globally. AIDS is considered a pandemic—a disease outbreak which is present over a large area and is actively spreading.

HIV/AIDS has had a great impact on society, both as an illness and as a source of discrimination. The disease also has significant economic impacts. There are many misconceptions about HIV/AIDS such as the belief that it can be transmitted by casual non-sexual contact. The disease has also become subject to many controversies involving religion.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

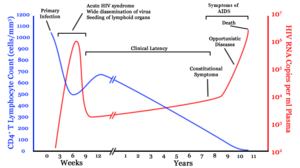

There are three main stages of HIV infection: acute infection, clinical latency and AIDS.

Acute Infection

The initial period following the contraction of HIV is called acute HIV, primary HIV or acute retroviral syndrome. Many individuals develop an influenza-like illness or a mononucleosis-like illness 2–4 weeks post exposure while others have no significant symptoms. Symptoms occur in 40–90% of cases and most commonly include fever, large tender lymph nodes, throat inflammation, a rash, headache, and/or sores of the mouth and genitals. The rash, which occurs in 20–50% of cases, presents itself on the trunk and is maculopapular, classically. Some people also develop opportunistic infections at this stage. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting or diarrhea may occur, as may neurological symptoms of peripheral neuropathy or Guillain-Barre syndrome. The duration of the symptoms varies, but is usually one or two weeks.

Due to their nonspecific character, these symptoms are not often recognized as signs of HIV infection. Even cases that do get seen by a family doctor or a hospital are often misdiagnosed as one of the many common infectious diseases with overlapping symptoms. Thus, it is recommended that HIV be considered in patients presenting an unexplained fever who may have risk factors for the infection.

Clinical Latency

The initial symptoms are followed by a stage called clinical latency, asymptomatic HIV, or chronic HIV. Without treatment, this second stage of the natural history of HIV infection can last from about three years to over 20 years (on average, about eight years). While typically there are few or no symptoms at first, near the end of this stage many people experience fever, weight loss, gastrointestinal problems and muscle pains. Between 50 and 70% of people also develop persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, characterized by unexplained, non-painful enlargement of more than one group of lymph nodes (other than in the groin) for over three to six months.

Although most HIV-1 infected individuals have a detectable viral load and in the absence of treatment will eventually progress to AIDS, a small proportion (about 5%) retain high levels of CD4+ T cells (T helper cells) without antiretroviral therapy for more than 5 years. These individuals are classified as HIV controllers or long-term nonprogressors (LTNP). Another group is those who also maintain a low or undetectable viral load without anti-retroviral treatment who are known as “elite controllers” or “elite suppressors”. They represent approximately 1 in 300 infected persons.

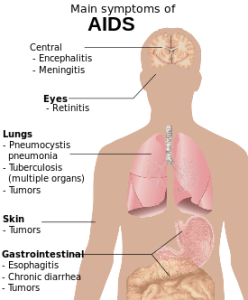

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is defined in terms of either a CD4+ T cell count below 200 cells per µL or the occurrence of specific diseases in association with an HIV infection. In the absence of specific treatment, around half of people infected with HIV develop AIDS within ten years. The most common initial conditions that alert to the presence of AIDS are pneumocystis pneumonia (40%), cachexia in the form of HIV wasting syndrome (20%) and esophageal candidiasis. Other common signs include recurring respiratory tract infections.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is defined in terms of either a CD4+ T cell count below 200 cells per µL or the occurrence of specific diseases in association with an HIV infection. In the absence of specific treatment, around half of people infected with HIV develop AIDS within ten years. The most common initial conditions that alert to the presence of AIDS are pneumocystis pneumonia (40%), cachexia in the form of HIV wasting syndrome (20%) and esophageal candidiasis. Other common signs include recurring respiratory tract infections.

Opportunistic infections may be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites that are normally controlled by the immune system. Which infections occur partly depends on what organisms are common in the person’s environment. These infections may affect nearly every organ system.

People with AIDS have an increased risk of developing various viral induced cancers including: Kaposi’s sarcoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and cervical cancer. Kaposi’s sarcoma is the most common cancer occurring in 10 to 20% of people with HIV. The second most common cancer is lymphoma which is the cause of death of nearly 16% of people with AIDS and is the initial sign of AIDS in 3 to 4%. Both these cancers are associated with human herpesvirus 8. Cervical cancer occurs more frequently in those with AIDS due to its association with human papillomavirus (HPV).

Additionally, people with AIDS frequently have systemic symptoms such as prolonged fevers, sweats (particularly at night), swollen lymph nodes, chills, weakness, and weight loss. Diarrhea is another common symptom present in about 90% of people with AIDS. They can also be affected by diverse psychiatric and neurological symptoms independent of opportunistic infections and cancers.

TRANSMISSION

HIV is transmitted by three main routes: sexual contact, exposure to infected body fluids or tissues, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding (known as vertical transmission). There is no risk of acquiring HIV if exposed to feces, nasal secretions, saliva, sputum, sweat, tears, urine, or vomit unless these are contaminated with blood. It is possible to be co-infected by more than one strain of HIV—a condition known as HIV superinfection.

Sexual

The most frequent mode of transmission of HIV is through sexual contact with an infected person. The majority of all transmissions worldwide occur through heterosexual contacts (i.e. sexual contacts between people of the opposite sex); however, the pattern of transmission varies significantly among countries. In the United States, as of 2009, most sexual transmission occurred in men who had sex with men, with this population accounting for 64% of all new cases.

As regards unprotected heterosexual contacts, estimates of the risk of HIV transmission per sexual act appear to be four to ten times higher in low-income countries than in high-income countries. In low-income countries, the risk of female-to-male transmission is estimated as 0.38% per act, and of male-to-female transmission as 0.30% per act; the equivalent estimates for high-income countries are 0.04% per act for female-to-male transmission, and 0.08% per act for male-to-female transmission.The risk of transmission from anal intercourse is especially high, estimated as 1.4–1.7% per act in both heterosexual and homosexual contacts.[35][36] While the risk of transmission from oral sex is relatively low, it is still present. The risk from receiving oral sex has been described as “nearly nil” however a few cases have been reported. The per-act risk is estimated at 0–0.04% for receptive oral intercourse. In settings involving prostitution in low income countries, risk of female-to-male transmission has been estimated as 2.4% per act and male-to-female transmission as 0.05% per act.

Risk of transmission increases in the presence of many sexually transmitted infections and genital ulcers. Genital ulcers appear to increase the risk approximately fivefold. Other sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and bacterial vaginosis, are associated with somewhat smaller increases in risk of transmission.

The viral load of an infected person is an important risk factor in both sexual and mother-to-child transmission. During the first 2.5 months of an HIV infection a person’s infectiousness is twelve times higher due to this high viral load. If the person is in the late stages of infection, rates of transmission are approximately eightfold greater.

Commercial sex workers (including those in pornography) have an increased rate of HIV. Rough sex can be a factor associated with an increased risk of transmission. Sexual assault is also believed to carry an increased risk of HIV transmission as condoms are rarely worn, physical trauma to the vagina or rectum is likely, and there may be a greater risk of concurrent sexually transmitted infections.

Body Fluids

The second most frequent mode of HIV transmission is via blood and blood products. Blood-borne transmission can be through needle-sharing during intravenous drug use, needle stick injury, transfusion of contaminated blood or blood product, or medical injections with unsterilised equipment. The risk from sharing a needle during drug injection is between 0.63 and 2.4% per act, with an average of 0.8%. The risk of acquiring HIV from a needle stick from an HIV-infected person is estimated as 0.3% (about 1 in 333) per act and the risk following mucus membrane exposure to infected blood as 0.09% (about 1 in 1000) per act. In the United States intravenous drug users made up 12% of all new cases of HIV in 2009, and in some areas more than 80% of people who inject drugs are HIV positive.

HIV is transmitted in About 93% of blood transfusions involving infected blood. In developed countries the risk of acquiring HIV from a blood transfusion is extremely low (less than one in half a million) where improved donor selection and HIV screening is performed; for example, in the UK the risk is reported at one in five million. In low income countries, only half of transfusions may be appropriately screened (as of 2008), and it is estimated that up to 15% of HIV infections in these areas come from transfusion of infected blood and blood products, representing between 5% and 10% of global infections.

Unsafe medical injections play a significant role in HIV spread in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2007, between 12 and 17% of infections in this region were attributed to medical syringe use. The World Health Organisation estimates the risk of transmission as a result of a medical injection in Africa at 1.2%. Significant risks are also associated with invasive procedures, assisted delivery, and dental care in this area of the world.

People giving or receiving tattoos, piercings, and scarification are theoretically at risk of infection but no confirmed cases have been documented. It is not possible for mosquitoes or other insects to transmit HIV.

Mother-To-Child

HIV can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, during delivery, or through breast milk. This is the third most common way in which HIV is transmitted globally. In the absence of treatment, the risk of transmission before or during birth is around 20% and in those who also breastfeed 35%. As of 2008, vertical transmission accounted for about 90% of cases of HIV in children. With appropriate treatment the risk of mother-to-child infection can be reduced to about 1%. Preventive treatment involves the mother taking antiretroviral during pregnancy and delivery, an elective caesarean section, avoiding breastfeeding, and administering antiretroviral drugs to the newborn. Many of these measures are however not available in the developing world. If blood contaminates food during pre-chewing it may pose a risk of transmission.

VIROLOGY

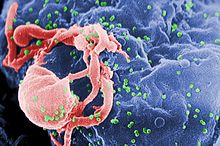

HIV is the cause of the spectrum of disease known as HIV/AIDS. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells.

HIV is the cause of the spectrum of disease known as HIV/AIDS. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells.

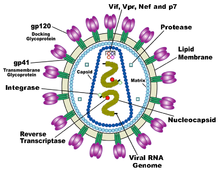

HIV is a member of the genus Lentivirus, part of the family Retroviridae. Lentiviruses share many morphological and biological characteristics. Many species of mammals are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses with a long incubation period. Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon entry into the target cell, the viral RNA genome is converted (reverse transcribed) into double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase that is transported along with the viral genome in the virus particle. The resulting viral DNA is then imported into the cell nucleus and integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded integrase and host co-factors. Once integrated, the virus may become latent, allowing the virus and its host cell to avoid detection by the immune system. Alternatively, the virus may be transcribed, producing new RNA genomes and viral proteins that are packaged and released from the cell as new virus particles that begin the replication cycle anew.

Two types of HIV have been characterized: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that was originally discovered (and initially referred to also as LAV or HTLV-III). It is more virulent, more infective, and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. The lower infectivity of HIV-2 as compared with HIV-1 implies that fewer people exposed to HIV-2 will be infected per exposure. Because of its relatively poor capacity for transmission, HIV-2 is largely confined to West Africa.

After the virus enters the body there is a period of rapid viral replication, leading to an abundance of virus in the peripheral blood. During primary infection, the level of HIV may reach several million virus particles per milliliter of blood. This response is accompanied by a marked drop in the number of circulating CD4+ T cells. The acute viremia is almost invariably associated with activation of CD8+ T cells, which kill HIV-infected cells, and subsequently with antibody production, or seroconversion. The CD8+ T cell response is thought to be important in controlling virus levels, which peak and then decline, as the CD4+ T cell counts recover. A good CD8+ T cell response has been linked to slower disease progression and a better prognosis, though it does not eliminate the virus.

The pathophysiology of AIDS is complex. Ultimately, HIV causes AIDS by depleting CD4+ T cells. This weakens the immune system and allows opportunistic infections. T cells are essential to the immune response and without them, the body cannot fight infections or kill cancerous cells. The mechanism of CD4+ T cell depletion differs in the acute and chronic phases. During the acute phase, HIV-induced cell lysis and killing of infected cells by cytotoxic T cells accounts for CD4+ T cell depletion, although apoptosis may also be a factor. During the chronic phase, the consequences of generalized immune activation coupled with the gradual loss of the ability of the immune system to generate new T cells appear to account for the slow decline in CD4+ T cell numbers.

Although the symptoms of immune deficiency characteristic of AIDS do not appear for years after a person is infected, the bulk of CD4+ T cell loss occurs during the first weeks of infection, especially in the intestinal mucosa, which harbors the majority of the lymphocytes found in the body. The reason for the preferential loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells is that the majority of mucosal CD4+ T cells express the CCR5 protein which HIV uses as a co-receptor to gain access to the cells, whereas only a small fraction of CD4+ T cells in the bloodstream do so.

HIV seeks out and destroys CCR5 expressing CD4+ T cells during acute infection. A vigorous immune response eventually controls the infection and initiates the clinically latent phase. CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissues remain particularly affected. Continuous HIV replication causes a state of generalized immune activation persisting throughout the chronic phase. Immune activation, which is reflected by the increased activation state of immune cells and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, results from the activity of several HIV gene products and the immune response to ongoing HIV replication. It is also linked to the breakdown of the immune surveillance system of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier caused by the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells during the acute phase of disease.

DIAGNOSIS

HIV/AIDS is diagnosed via laboratory testing and then staged based on the presence of certain signs or symptoms. HIV screening is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force for all people 15 years to 65 years of age including all pregnant women. Additionally testing is recommended for all those at high risk, which includes anyone diagnosed with a sexually transmitted illness. In many areas of the world a third of HIV carriers only discover they are infected at an advanced stage of the disease when AIDS or severe immunodeficiency has become apparent.

HIV/AIDS is diagnosed via laboratory testing and then staged based on the presence of certain signs or symptoms. HIV screening is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force for all people 15 years to 65 years of age including all pregnant women. Additionally testing is recommended for all those at high risk, which includes anyone diagnosed with a sexually transmitted illness. In many areas of the world a third of HIV carriers only discover they are infected at an advanced stage of the disease when AIDS or severe immunodeficiency has become apparent.

HIV Testing

Most people infected with HIV develop specific antibodies (i.e. seroconvert) within three to twelve weeks of the initial infection. Diagnosis of primary HIV before seroconversion is done by measuring HIV-RNA or p24 antigen.Positive results obtained by antibody or PCR testing are confirmed either by a different antibody or by PCR.

Antibody tests in children younger than 18 months are typically inaccurate due to the continued presence of maternal antibodies. Thus HIV infection can only be diagnosed by PCR testing for HIV RNA or DNA, or via testing for the p24 antigen. Much of the world lacks access to reliable PCR testing and many places simply wait until either symptoms develop or the child is old enough for accurate antibody testing. In sub-Saharan Africa as of 2007–2009 between 30 and 70% of the population was aware of their HIV status. In 2009, between 3.6 and 42% of men and women in Sub-Saharan countries were tested which represented a significant increase compared to previous years.

Classifications of HIV Infection

Two main clinical staging systems are used to classify HIV and HIV-related disease for surveillance purposes: the WHO disease staging system for HIV infection and disease, and the CDC classification system for HIV infection. The CDC’s classification system is more frequently adopted in developed countries. Since the WHO’s staging system does not require laboratory tests, it is suited to the resource-restricted conditions encountered in developing countries, where it can also be used to help guide clinical management. Despite their differences, the two systems allow comparison for statistical purposes.

The World Health Organization first proposed a definition for AIDS in 1986. Since then, the WHO classification has been updated and expanded several times, with the most recent version being published in 2007. The WHO system uses the following categories:

- Primary HIV infection: May be either asymptomatic or associated with acute retroviral syndrome.

- Stage I: HIV infection is asymptomatic with a CD4+ T cell count (also known as CD4 count) greater than 500 per microlitre (µl or cubic mm) of blood. May include generalized lymph node enlargement.

- Stage II: Mild symptoms which may include minor mucocutaneous manifestations and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. A CD4 count of less than 500/µl.

- Stage III: Advanced symptoms which may include unexplained chronic diarrhea for longer than a month, severe bacterial infections including tuberculosis of the lung, and a CD4 count of less than 350/µl.

- Stage IV or AIDS: severe symptoms which include toxoplasmosis of the brain, candidiasis of the esophagus, trachea, bronchi or lungs and Kaposi’s sarcoma. A CD4 count of less than 200/µl.

The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention also created a classification system for HIV, and updated it in 2008. This system classifies HIV infections based on CD4 count and clinical symptoms, and describes the infection in three stages:

- Stage 1: CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/µl and no AIDS defining conditions

- Stage 2: CD4 count 200 to 500 cells/µl and no AIDS defining conditions

- Stage 3: CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/µl or AIDS defining conditions

- Unknown: if insufficient information is available to make any of the above classifications

For surveillance purposes, the AIDS diagnosis still stands even if, after treatment, the CD4+ T cell count rises to above 200 per µL of blood or other AIDS-defining illnesses are cured.

PREVENTION

Sexual Contact

Consistent condom use reduces the risk of HIV transmission by approximately 80% over the long term. When condoms are used consistently by a couple in which one person is infected, the rate of HIV infection is less than 1% per year. There is some evidence to suggest that female condoms may provide an equivalent level of protection. Application of a vaginal gel containing tenofovir (a reverse transcriptase inhibitor) immediately before sex seems to reduce infection rates by approximately 40% among African women. By contrast, use of the spermicide nonoxynol-9 may increase the risk of transmission due to its tendency to cause vaginal and rectal irritation. Circumcision in Sub-Saharan Africa “reduces the acquisition of HIV by heterosexual men by between 38% and 66% over 24 months”. Based on these studies, the World Health Organization and UNAIDS both recommended male circumcision as a method of preventing female-to-male HIV transmission in 2007. Whether it protects against male-to-female transmission is disputed and whether it is of benefit in developed countries and among men who have sex with men is undetermined. Some experts fear that a lower perception of vulnerability among circumcised men may cause more sexual risk-taking behavior, thus negating its preventive effects.

Programs encouraging sexual abstinence do not appear to affect subsequent HIV risk. Evidence for a benefit from peer education is equally poor. Comprehensive sexual education provided at school may decrease high risk behavior. A substantial minority of young people continues to engage in high-risk practices despite knowing about HIV/AIDS, underestimating their own risk of becoming infected with HIV. It is not known whether treating other sexually transmitted infections is effective in preventing HIV.

Pre-Exposure

Treating people with HIV whose CD4 count ≥ 350cells/µL with antiretrovirals protects 96% of their partners from infection. This is about a 10 to 20 fold reduction in transmission risk. Pre-exposure prophylaxis with a daily dose of the medications tenofovir, with or without emtricitabine, is effective in a number of groups including men who have sex with men, couples where one is HIV positive, and young heterosexuals in Africa. It may also be effective in intravenous drug users with a study finding a decrease in risk of 0.7 to 0.4 per 100 person years.

Universal precautions within the health care environment are believed to be effective in decreasing the risk of HIV. Intravenous drug use is an important risk factor and harm reduction strategies such as needle-exchange programmes and opioid substitution therapy appear effective in decreasing this risk.

Post-Exposure

A course of antiretrovirals administered within 48 to 72 hours after exposure to HIV-positive blood or genital secretions is referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). The use of the single agent zidovudine reduces the risk of a HIV infection five-fold following a needle-stick injury. As of 2013, the prevention regime recommended in the United States consists of three medications—tenofovir, emtricitabine and raltegravir—as this may reduce the risk further.

PEP treatment is recommended after a sexual assault when the perpetrator is known to be HIV positive, but is controversial when their HIV status is unknown. The duration of treatment is usually four weeks and is frequently associated with adverse effects—where zidovudine is used, about 70% of cases result in adverse effects such as nausea (24%), fatigue (22%), emotional distress (13%) and headaches (9%).

Mother-To-Child

Programs to prevent the vertical transmission of HIV (from mothers to children) can reduce rates of transmission by 92–99%. This primarily involves the use of a combination of antiviral medications during pregnancy and after birth in the infant and potentially includes bottle feeding rather than breastfeeding. If replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe, mothers should avoid breastfeeding their infants; however exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life if this is not the case. If exclusive breastfeeding is carried out, the provision of extended antiretroviral prophylaxis to the infant decreases the risk of transmission.

Vaccination

As of 2012 there is no effective vaccine for HIV or AIDS. A single trial of the vaccine RV 144 published in 2009 found a partial reduction in the risk of transmission of roughly 30%, stimulating some hope in the research community of developing a truly effective vaccine. Further trials of the RV 144 vaccine are ongoing.

MANAGEMENT

There is currently no cure or effective HIV vaccine. Treatment consists of high active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) which slows progression of the disease and as of 2010 more than 6.6 million people were taking them in low and middle income countries. Treatment also includes preventive and active treatment of opportunistic infections.

There is currently no cure or effective HIV vaccine. Treatment consists of high active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) which slows progression of the disease and as of 2010 more than 6.6 million people were taking them in low and middle income countries. Treatment also includes preventive and active treatment of opportunistic infections.

Antiviral Therapy

Current HAART options are combinations (or “cocktails”) consisting of at least three medications belonging to at least two types, or “classes,” of antiretroviral agents. Initially treatment is typically a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) plus two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). Typical NRTIs include: zidovudine (AZT) or tenofovir (TDF) and lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC). Combinations of agents which include a protease inhibitors (PI) are used if the above regime loses effectiveness.

When to start antiretroviral therapy is subject to debate. The World Health Organization, European guidelines and the United States recommends antiretrovirals in all adolescents, adults and pregnant women with a CD4 count less than 350/µl or those with symptoms regardless of CD4 count. This is supported by the fact that beginning treatment at this level reduces the risk of death. The United States in addition recommends them for all HIV-infected people regardless of CD4 count or symptoms; however it makes this recommendation with less confidence for those with higher counts. While the WHO also recommends treatment in those who are co-infected with tuberculosis and those with chronic active hepatitis B. Once treatment is begun it is recommended that it is continued without breaks or “holidays”. Many people are diagnosed only after treatment ideally should have begun. The desired outcome of treatment is a long term plasma HIV-RNA count below 50 copies/mL. Levels to determine if treatment is effective are initially recommended after four weeks and once levels fall below 50 copies/mL checks every three to six months are typically adequate. Inadequate control is deemed to be greater than 400 copies/mL. Based on these criteria treatment is effective in more than 95% of people during the first year.

Benefits of treatment include a decreased risk of progression to AIDS and a decreased risk of death. In the developing world treatment also improves physical and mental health. With treatment there is a 70% reduced risk of acquiring tuberculosis. Additional benefits include a decreased risk of transmission of the disease to sexual partners and a decrease in mother-to-child transmission. The effectiveness of treatment depends to a large part on compliance. Reasons for non-adherence include poor access to medical care, inadequate social supports, mental illness and drug abuse. The complexity of treatment regimens (due to pill numbers and dosing frequency) and adverse effects may reduce adherence. Even though cost is an important issue with some medications, 47% of those who needed them were taking them in low and middle income countries as of 2010 and the rate of adherence is similar in low-income and high-income countries.

Specific adverse events are related to the agent taken. Some relatively common ones include: lipodystrophy syndrome, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus especially with protease inhibitors. Other common symptoms include diarrhea, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Newer recommended treatments are associated with fewer adverse effects. Certain medications may be associated with birth defects and therefore may be unsuitable for women hoping to have children.

Treatment recommendations for children are slightly different from those for adults. In the developing world, as of 2010, 23% of children who were in need of treatment had access. Both the World Health Organization and the United States recommend treatment for all children less than twelve months of age. The United States recommends in those between one year and five years of age treatment in those with HIV RNA counts of greater than 100,000 copies/mL, and in those more than five years treatments when CD4 counts are less than 500/µl.

Opportunistic Infections

Measures to prevent opportunistic infections are effective in many people with HIV/AIDS. In addition to improving current disease, treatment with antiretrovirals reduces the risk of developing additional opportunistic infections. Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is advised for all people at risk of HIV before they become infected; however it may also be given after infection. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis between four and six weeks of age and ceasing breastfeeding in infants born to HIV positive mothers is recommended in resource limited settings. It is also recommended to prevent PCP when a person’s CD4 count is below 200 cells/uL and in those who have or have previously had PCP. People with substantial immunosuppression are also advised to receive prophylactic therapy for toxoplasmosis and Cryptococcus meningitis. Appropriate preventive measures have reduced the rate of these infections by 50% between 1992 and 1997.

Alternative Medicine

In the US, approximately 60% of people with HIV use various forms of complementary or alternative medicine,even though the effectiveness of most of these therapies has not been established. With respect to dietary advice and AIDS some evidence has shown a benefit from micronutrient supplements. Evidence for supplementation with selenium is mixed with some tentative evidence of benefit. There is some evidence that vitamin A supplementation in children reduces mortality and improves growth. In Africa in nutritionally compromised pregnant and lactating women a multivitamin supplementation has improved outcomes for both mothers and children. Dietary intake of micronutrients at RDA levels by HIV-infected adults is recommended by the World Health Organization. The WHO further states that several studies indicate that supplementation of vitamin A, zinc, and iron can produce adverse effects in HIV positive adults. There is not enough evidence to support the use of herbal medicines.